|

International Peace Initiatives: The conflict situations in some parts of the globe today particularly in some parts of Africa in recent years have posed serious challenges to peace builders not only in those countries affected, but also across the international community. The devastating effects of these conflicts such as killings, maimings, kidnappings of innocent citizens and foreigners alike, destruction of human and natural resources, unlawful arrests and detention of innocent citizens have become a global concern to peace builders, citizens and the governments of the affected countries. Some conflicts can arise within a country out of economic, religious, cultural, or ethnic and environmental differences. Such conflicts are special kinds of conflicts and require specific approaches. In some countries and cultures of Africa, culture becomes the way of life a group creates during the course of its history. It is the way its members think and behave. It includes the values and beliefs they hold, social practices and structures influencing their conduct (customs, food, art, dress, etc.) and the languages they may speak. In some cultures in Africa, parties prefer to communicate through a go-between or third party because direct confrontation may hurt or impede the relationship. Some parties may prefer to talk to a third party who will give suggestions and may act as intermediaries. Whereas in some other cultures, dealing directly with the other party to a conflict is ideal; talking to others may be seen as gossip or increasing the conflict unnecessarily. A third party may be asked to intervene if it feels like they will help ease the already tense situation. CMMS believes that the local actors who are directly

involved in a conflict or war path are critical to peace-building

efforts, if progress is to be made in attaining the needed peace.

Our aim is to ensure that these actors in the dispute are empowered

to make decisions, and not making the decisions for them. Through

training in Alternative Dispute Resolution among actors in a conflict,

we will locate, support and empower and work with local actors as

they deal with conflicts in their communities. What is Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)?The term "alternative dispute resolution" or "ADR" is often used to describe a wide variety of dispute resolution mechanisms that are short of, or alternative to, full-scale court processes. The term can refer to everything from facilitated settlement negotiations in which disputants are encouraged to negotiate directly with each other prior to some other legal process, to arbitration systems or mini-trials that look and feel very much like a courtroom process. Processes designed to manage community tension or facilitate community development issues can also be included within the rubric of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). ADR systems may be generally categorized as negotiation, conciliation/mediation, or arbitration systems. Negotiation systems create a structure to encourage and facilitate direct negotiation between parties to a dispute, without the intervention of a third party. Mediation and conciliation systems are very similar in that they interject a third party between the disputants, either to mediate a specific dispute or to reconcile their relationship. Mediators and conciliators may simply facilitate communication, or may help direct and structure a settlement, but they do not have the authority to decide or rule on a settlement. Arbitration systems authorize a third party to decide how a dispute should be resolved. It is important to distinguish between binding and non-binding forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). Negotiation, mediation, and conciliation programmes are non-binding, and depend on the willingness of the parties to reach a voluntary agreement. Arbitration programmes may be either binding or non-binding. Binding arbitration produces a third party decision that the disputants must follow even if they disagree with the result, much like a judicial decision. Non-binding arbitration produces a third party decision that the parties may reject. It is also important to distinguish between mandatory processes and voluntary processes. Some judicial systems require litigants to negotiate, conciliate, mediate, or arbitrate prior to court action. ADR processes may also be required as part of a prior contractual agreement between parties. In voluntary processes, submission of a dispute to an ADR process depends entirely on the will of the parties. Aspects of ADR and Peace BuildingCollaborative and Adversarial Models of JusticeAdversarial proceedings such as litigation/adjudication are necessary and appropriate for serious crimes and for some types of offenders. They are associated with transparence, deterrence, retribution, rehabilitation, public denunciation, vindication, and safety, if only during the period of time individual offenders are incarcerated. For many less serious crimes committed by young person and/or first time offenders, these benefits may be outweighed by their costs. These include:

Unlike adversarial proceedings, alternative dispute resolution procedures such as mediation and restorative justice:

MediationIn their book, Conflict Resolution: An Introductory Text (2005), authors Ellis and Anderson define mediation as a process in which one or more third parties facilitate healing, story-telling, negotiations, communication and problem-solving between parties-in-conflict who make decisions on outcomes. Self-determination is the heart of mediation. The parties are authors of their own fate. Because the parties themselves create the terms of agreements, they are more likely to conform to them than if the terms of agreements were created by others and they were ordered to comply with them. Of course, if parties-in-conflict can settle conflicts through negotiation, they would also be authors of their own fate, and to a higher degree, because no facilitative third party was involved. The reality is that negotiations frequently fail because parties involved in resource, values and identity conflicts are often unable or unwilling to negotiate a settlement. At this point, the parties can select from a menu of adversarial (e.g. use of force, litigation, arbitration) procedures, or a collaborative/consensual/problem-solving procedure such as mediation. The presumptive Rule of Mediation states that mediation is, or should be, the first alternative selected save for the presence of specified exclusions. These include, where a serious (indictable) crime has been committed and punishment is warranted, or where one or both parties seek public vindication or set a precedent. Compared with litigation-adjudication and arbitration, mediation is far more likely to yield a "Wise Agreement".

A wise agreement is one that has the following attributes:

Restorative JusticeRestorative justice has been defined as a community-based response to criminal conduct and wrong-doing that brings together the victim, the offender and community members with a view to repairing the harm caused by such conduct". Restorative Justice is an innovative way of responding to conflict-related harmful conduct that focuses on relationships among victims, wrong-doers/offenders and community members. It is grounded in how individuals actually experience conflict rather than in conflicts as they are framed in legal language. As it is legally framed, conflict is defined as harms against the state or the individual, and always involves two parties, the accused and the state or the offender and the victim. As it is experienced, many conflicts involve multiple parties and conflict is defined, not in terms of harms against the state, but in terms of harms against human beings. Specifically, crime occurs when the actions of one party toward another are defined as being so far outside the bounds of what is commonly regarded as normal and appropriate that it merits some form of response. The response defines what is right and wrong and in so doing, reinforces shared moral sentiments and traditional values. Crime/conflict then, represents both a challenge and an opportunity for moral growth. Restorative justice rests on the premise that the most effective response to criminal and other wrongful acts is to repair the harm done by them. Specifically, restorative justice aims at the restoration of relationships built on trust, respect and dignity. Communities characterized by the predominance of such relationships are healthy, harmonious communities. The five pillars upon which restorative justice rests are:

A Brief History of ADRDispute resolution outside of courts is not new; societies world-over have long used non-judicial, indigenous methods to resolve conflicts. What is new is the extensive promotion and proliferation of ADR models, wider use of court-connected ADR, and the increasing use of ADR as a tool to realize goals broader than the settlement of specific disputes. The ADR movement in the United States was launched in the 1970s, beginning as a social movement to resolve community-wide civil rights disputes through mediation, and as a legal movement to address increased delay and expense in litigation arising from an overcrowded court system. Ever since, the legal ADR movement in the United States has grown rapidly, and has evolved from experimentation to institutionalization with the support of the American Bar Association, academics, courts, the U.S. Congress and state governments. Innovations in ADR models, expansion of government-mandated, court-based ADR in state and federal systems, and increased interest in ADR by disputants has made the United States the richest source of experience in court connected ADR. While the court-connected ADR movement flourished in the U.S. legal community, other ADR advocates saw the use of ADR methods outside the court system as a means to generate solutions to complex problems that would better meet the needs of disputants and their communities, reduce reliance on the legal system, strengthen local civic institutions, preserve disputants' relationships, and teach alternatives to violence or litigation for dispute settlement. In 1976, the San Francisco Community Boards programme was established to further such goals. This experiment has spawned a variety of community-based ADR projects, such as school based peer mediation programmes and neighborhood justice centers. In the 1980s, demand for ADR in the commercial sector began to grow as part of an effort to find more efficient and effective alternatives to litigation. Since this time, the use of private arbitration, mediation and other forms of ADR in the business setting has risen dramatically, accompanied by an explosion in the number of private firms offering ADR services. The move from experimentation to institutionalization in the ADR field has also affected administrative rule-making and litigation practice. Laws now in place authorize and encourage agencies to use negotiation and other forms of ADR in rulemaking, public consultation, and administrative dispute resolution. Internationally, the ADR movement has also taken off in both developed and developing countries. ADR models may be straight-forward imports of processes found in the United States, Canada and other developed countries or hybrid experiments mixing ADR models with elements of traditional dispute resolution. ADR processes are being implemented to meet a wide range of social, legal, commercial, and political goals. In the developing world, a number of countries are engaging in the ADR experiment, including Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, the Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, and Uruguay. Nigeria should not be an exception and the Nigeria Police should take the lead in experimenting the ADR pilot project in Nigeria, now that the country is a purely democratically led country. ADR in Socio Development ContextConflict grounded in social, structural, cultural, political and economic factors is endemic in all societies. At the same time, recurring conflicts with more serious consequences are more likely to be present in some societies than in others. The government of Nigeria is concerned about the deleterious consequences of recurring conflicts over the distribution of resources, secession, opposing religious values as well as recurring conflicts between rival youth street gangs. The government's concern is expressed in its desire to settle or resolve such conflicts in ways that promote a more peaceful Nigeria without increasing the already heavy burden placed on adversarial criminal and civil justice systems. The implementation of collaborative alternative dispute resolution procedures will promote the achievement of both objectives. The increasing importance of dispute resolution in the African context is a reflection of the global growth in ADR and what are the preferred methods of resolving disputes, a trend that is likely to continue into the 21st Century. Since the 1970s there has been a surge in the participation in alternative dispute resolution by less developed countries. It is therefore important for officials in developing countries to be aware of the issues and problems involved in the various stages of ADR programmes. There are several methods available for resolving disputes between two parties. The first and most important method is through the courts. When a dispute arises between two parties belonging to the same country, there is an established forum available for the resolution of the same. The parties can get the said dispute resolved through the courts established by law in that country. Generally, this has been the most common method employed by the citizens of a country for the resolution of their disputes with the fellow citizens. Alternative dispute resolution methods are becoming more popular for resolution of disputes between parties. So much so that some persons have started calling them "appropriate" dispute resolution methods rather than "alternative" dispute resolution methods. The alternative dispute resolution methods offer distinct advantages over litigation. Alternative dispute resolution encompasses a variety of methods for the resolution of disputes between the parties. The availability or deployment of any particular method of alternative dispute resolution in any specific case depends on a number of factors. The clause relating to alternative dispute resolution in the agreement between the parties, the availability of persons well versed in the process of alternative dispute resolution, the support provided by the legal system of a country to the alternative dispute resolution methods, the national or international institutional framework for alternative dispute resolution, the availability of necessary infrastructure facilities, etc., play a significant role in the selection of any particular method of the resolution of dispute. Dispute Resolution Mechanisms and Constitutional Rights in Sub-Saharan AfricaDisagreements and misunderstanding are key characteristics of human relationships whether the relationship is a domestic, national or international one. The potential for disputes is even higher where the parties are from different cultural, economic and political backgrounds with different legal systems. Since disputes are such a critical part of human relationships, many countries have mechanisms to resolve them in a manner, which maintains the cohesion, economic and political stability of the state. This is particularly so with regard to disputes related to commerce because commerce is the engine of growth. The adjudicatory system of dispute resolution or the civil court system as we know it today evolved to resolve disputes among citizens. In each country of the world, the local court system has a history of development behind it but modern court systems all over the world have been influenced by the common law system which originated from England because England was at one time the dominant world power exporting its culture, ideas and system of governance to the rest of the world through the activities of its famous explorers. This adjudicatory or common law system is what has been exported to many developing countries, which were former colonies of Britain. In particular, many sub Saharan African countries which were colonies of Great Britain have retained the system of dispute resolution inherited from the former colonial governments. The point made above is not to say that African nations did not have their own indigenous system of dispute resolution before the advent of the colonial government. In fact as we shall see, African traditional system of dispute resolution is closer in nature and character to arbitration than to the colonial system of adjudication. But since African lawyers are trained in the common law system of adjudication which is integrated into the system of governance by the constitution backed by the establishment of courts, judges, the rules of procedures and the enforcement of the judgments, African lawyers have come to rely on and trust the common law system more than any other form of dispute resolution. But the common law adjudicatory system of dispute resolution is widely known to be fraught with a myriad of shortcomings especially when applied to the resolution of commercial disputes. These shortcomings range from the delay in the process of litigation, the cumbersome rules of procedure, the corruption of judges and court officials in some countries, the cost of litigation, the publicity which goes with the hearing and the judgment etc. Whereas developed countries have managed to develop dispute resolution mechanisms which reduce the impact of the shortcomings identified here and conform to modernity and the demands of economic growth, many developing countries especially in Africa are still saddled with old forms of adjudication which they inherited from colonial governments. One of the reasons for this is the conservatism of lawyers in these countries who prefer to resolve disputes within their familiar adjudicatory system in spite of all the problems. Another reason is that they are not familiar with the modern forms of dispute resolution. In spite of the imposition of the foreign system of adjudication and its promotion by British trained African lawyers, many Africans still believe in and use the traditional system of dispute resolution although its scope and application to commercial disputes is limited. Alternative Forms of Dispute ResolutionThe shortcomings in the adjudicatory system of resolving disputes led to the emergence of other methods of dispute resolution now popularly referred to as ADR. The value of ADR over and above the common adjudicatory system is that any of the techniques can be implemented very early in the dispute thereby giving the parties an opportunity to air their views and to involve decision makers within their respective organizations long before the subject of dispute eats deep into the fabric of the relationship and cause irreparable damage. African Customary System of Dispute ResolutionCustomary law is generally known to be the accepted norm of usage in any community. A community may accept certain customs as binding on them. In Africa, such customary laws may be accepted by members of particular ethnic groups and may be regarded as ethnic customary law. Customary law is unwritten and one of it's most commendable characteristics is its flexibility, apart from the fact that it is the accepted norm of usage. In one Nigerian case, the court said: "One of the most striking features of West African native custom ... is its flexibility; it appears to have been always subject to motives of expediency, and it shows unquestionable adaptability to altered circumstances without entirely losing its character." ADR methods vary and their processes overlap but are all designed as alternatives to litigation and complement arbitration which is the most popular form of ADR. The methods include negotiation, early neutral evaluation or neutral fact finding, conciliation, mediation, mini trial, med-arb etc. The key factor is that all these methods are designed to assist the parties resolve their differences in a manner that is creative and most suited to the particular dispute. Some people see ADR methods as supplanting the adjudicatory system but if considered from the angle that the courts in many jurisdictions are unable to resolve all disputes in a manner appealing to litigants, and then ADR methods will be accepted as complementary to the litigation system of governance. The role was taken up by the elders or the chief and was meant to maintain social cohesion. In its operation, African dispute resolution was very much like arbitration in that resolution of disputes was not adversarial. Any person who is concerned that a dispute between the parties threatened the peace of the community could initiate the process. In the process, parties have the opportunity to state their case and their expectation but the final decision is that of the elders. Whereas the western type arbitration is attractive because of its private nature, customary arbitration is not private but is organized to socialize the whole society, therefore, the community is present. Another distinction is that the process is gender sensitive as such women were excluded from male driven communal dispute resolution. Parties could arise from the whole process and maintain their relationship and where one party got an award the whole society was witness and saw to it that it was enforced. Social exclusion or ostracism was a potent sanction for any erring party therefore enforcement of an award was not a problem. There are however several limitations of this process in modern times. One is that it is mostly applied to land and family disputes. It is hardly applicable to monetized commercial transactions and certainly not to transaction of an international character. Furthermore, it is community focused and does not contemplate transactions where the parties are from different cultural backgrounds. Although African dispute resolution mechanisms cannot be applied to commercial disputes except perhaps those dealing with community land, nevertheless, it offers an insight into the options available outside the adjudicatory system offered by the common law. By comparing it to arbitration and the parameters of litigation, lawyers, particularly government lawyers ought to be able to advise their governments on the need and basis for arbitration in commercial arrangements especially those of an international nature. And this is the purpose of our proposal. The Role of Nigeria in Peace Building, Conflict Resolution, and Peacekeeping since 1960Over the past twenty-five years, Nigeria has emerged from a relatively obscure position under colonial domination to a major power in international affairs. This position as well as the commitment underpinning it has been expressed more forcefully in the defense of Africa which, in cooperation with other countries within the continent and in the Diaspora, has helped in keeping alive the pan-African ideal. Between 1960 and 2005, Nigeria has been actively involved in various ways in the struggle against colonialism in Southern Africa; in demonstrating the cultural richness and diversity of Africa; in building and maintaining peace throughout the West African region; and in helping to establish, and continuing to support the Economic Community of West African States [ECOWAS (1975)] the Organization of African Unity [OAU (1963), now AU (2001)], the Non-Aligned Movement, and other organizations concerned with bringing peace to regions and peoples across the world. Nigeria's membership of the "Frontline States" during the struggle against Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa; its long-term chairmanship of the UN Special Committee against Apartheid; and its leadership of peacekeeping missions in Chad (1979-82), Liberia (1990-98), Sierra Leone (1996-00), Guinea Bissau (1998-00) and Cotê d'Ivoire (2000-Date) are all reflections of its commitment and role to peace building, peace keeping, and conflict resolution. Key Observations of ADRBelow are a number of the key observations with ADR programme implementation

If ADR appears feasible, it is important to ensure that the ADR programme involves needs assessment and identification of goals, adequate legal foundation, and effective local partnerships Key Features of ADR ApproachesAlthough the characteristics of negotiated settlement, conciliation, mediation, arbitration, and other forms of community justice vary, all share a few common elements of distinction from the formal judicial structure. These elements permit them to address development objectives in a manner different from judicial systems.

Benefits of ADR Programme

The ADR programme is designed to meet a wide variety of different goals. Some of these goals are directly related to improving the administration of justice and the settlement of disputes. Some are related to other development objectives, such the management of tensions and conflicts in communities, developing an efficient capacities and consensual ways to resolve disputes that will be critical to a social development, strengthening the rule of law. The training immediate expected outcomes are to: Within the context of rule of law initiatives, the ADR programme: In the context of other development objectives, the ADR programme: Experience suggests that ADR programmes can have a positive impact on social economic (sustainable) development objectives, although the extent of the impact is very much dependent on other conditions within the country and the fit of the design and implementation of the programme with the development objectives. Certificate In Dispute ResolutionWhat is Dispute Resolution:Having a disagreement with a neighbour, peers, roommate, friend, spouse, parents, siblings, co-worker or business associate can make an individual confused, afraid, unsecured, lose self esteem and angry. Sometimes, a small conflict can get worse, if not resolved, whether domestic or otherwise. Conflicts can be made worse by bringing in other conflicts from the past. It is important to deal with conflicts as they arise. Conflicts occur inside individuals, within on-going individuals and group relationships, and also between different individuals and groups (may be gangs). Conflicts affect relationships. People get angry and frustrated when their relationships fail. Miscommunication leads to wrong assumption and entrenched positions. People need help to break the cycle of violence and escalation that often sets in with conflict. Mediation is further seen as a voluntary meeting between the parties involved in a conflict where trained community volunteer mediators help the disputants resolve the conflict in such a way that is safe, fair and satisfactory for both parties. Alternative dispute resolution is both new and old. According to Mark Bennett and Michelle Herman: “it is a recent and explosively growing movement which seeks to reduce litigation, increase participants’ satisfactions, and control court congestion”. Many elements of modern ADR methods, however, have roots in ancient traditions of problem solving valued for centuries in a variety of cultures throughout this country and around the world. Since 90% of cases filed in courts can be predicted to settle, while less than 10% proceed to trial; negotiation is by far the most pervasive dispute resolution process. Therefore, in mediation, the mediators do not make a decision but help the parties promote the use of constructive problem solving skills through a structured process, which has been developed to enhance their ability to achieve a resolution, which is fair, satisfying and durable. ROLE OF CONFLICT MEDIATOR IN CONFLICTS A Mediator in this setting is a neutral third party who has been trained and assigned to facilitate a mediation process between two aggrieving parties in a conflict in such a way that is fair, safe and satisfactory for both parties. Here the mediator uses the interest-based approach, which asks what problems underlie or cause the conflict, what the parties need and want. The mediator uses good communication skills such as attentive listening, restating and clarifying what has been said by both parties, asking neutral and open ended questions, becomes sensitive to cultural, language, power differences, putting into consideration the socio-political dynamics of the parties’ culture, language and power power-base. The mediator should not be afraid to name differences and talk about power imbalances, such as inequalities. The mediator should be able to detect the underlying cause of the conflict through interaction with both parties without telling the parties what the conflict is. Validates each party and help each party or person to see the other’s point of view. Helps the parties to identify the points of disagreement and common interest. Diffuse anger while developing empathy between the disputants or rival parties or gangs Strives for Win-Win-Win Resolution always. By this the mediator focuses on finding solutions that meet the interests of both parties or gangs or individuals. Using this approach, the mediator tries to facilitate the process of finding solutions that meet all parties’ needs and wants. This approach generates the Win-Win Negotiation, which takes the interest based approach to solving the parties’ differences. By looking at what both parties want to achieve and finding creative ways of coming to a solution that both parties are happy with, you have nip the conflict in the bud (parties in this case could be rival gangs, neighbours, friends, associates, etc.) WHY MEDIATION? Mediation or Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is fast becoming the option of choice for managing conflicts, and preventing it from escalating to violent behaviour by the conflicting parties or gangs. When mediation is effectively used, it becomes a tool for crime prevention in our community. ADVANTAGES OF MEDIATION Mediation can turn conflicts into advantages if explored. Mediation can turn conflict into benefit for those who are in it. It could become a lesson for those who are yet to be in it as well. Below are some benefits that mediation could bring into conflicts.

CERTIFICATE COURSES IN "ALTERNATIVE Our flexible and responsive certificate program is designed for learners from all walks of life and educational backgrounds. The program is offered in an exciting and stimulating format and draws on the expertise of the finest dispute resolution practitioners and educators in the profession. Our classes blend lectures, interactive teaching models and role-playing techniques that are used exclusively in our program. Our students become engrossed in an invigorating and realistic learning process that provides them opportunities to experiment and to acquire their own distinct mediation styles. Co-Sponsor Canadian Multicultural Mediation Service (CMMS) is a community based conflict resolution service provider based in Canada. Since its inception, it has helped disputants in conflicts resolve their disputes through trained mediators who are specialized in the skill of problem solving. They resolve the conflicts in such a way that is safe, fair, unbiased and satisfactory for both parties who are in dispute. In the end, it will help restore, repair and build damaged relationships among individuals, families, groups, peers, associates, in our communities. Since its inception, it has helped thousands of disputants resolve their disputes, as our mandate is to help support and conduct research, and also to disseminate the results of the research on violence and conflict resolution in broad sense. Who Should Attend This program will be of interest to those who wish to become professional mediators in the field of their choice or who simply want to acquire specific skills for use in their current or future jobs. Our graduates include professionals working in administration, business, education, finance, government, healthcare, law, policing, real estate, prisons, faith organizations, community organization, correctional services, social work and several other disciplines. Admission Requirements and Prerequisites Certificate Candidates must have:

Program Structure and List of Courses The following topics will be covered in the Mediation Training: Section 1: Techniques and Skills: Defining Mediation:

Communication Skills for Mediators:

Win/Win Problem Solving:

Section 2: The Mediation Process Mediation Process:

Preparation and Assessment:

Special Topics:

Cultural Perspective in Mediation

Violence and Conflict Resolution

Section 3: Role-Plays Preparation Notes

Restorative Justice Victim Offender Mediation Victim-offender mediation training and skills development Victim-Offender mediation training and skills development training will offer state institutions (the courts, the judicial system) and public agents the ability to have different ways of dealing with the aftermath of a crime. The Restorative justice training programme will be offered to both agents of the state who refer offenders to them and to community workers who facilitate them. As there are at least five entry points ( pre-charge, post-charge, pre-sentence, post-sentence and parole-revocation) into the criminal justice system where offenders may be referred to a restorative justice programme, Victim-Offender mediation will be offered to Police officers, Customary Court Judges, Warders, Correctional Staff and Parole Officers, Road Safety Officers, Traffic Wardens, etc. Programme Content: The following topics will be covered in the Restorative Justice – Victim Offender Mediation Training: Section I

Section II

Section III

Section IV

Section V

Section VI

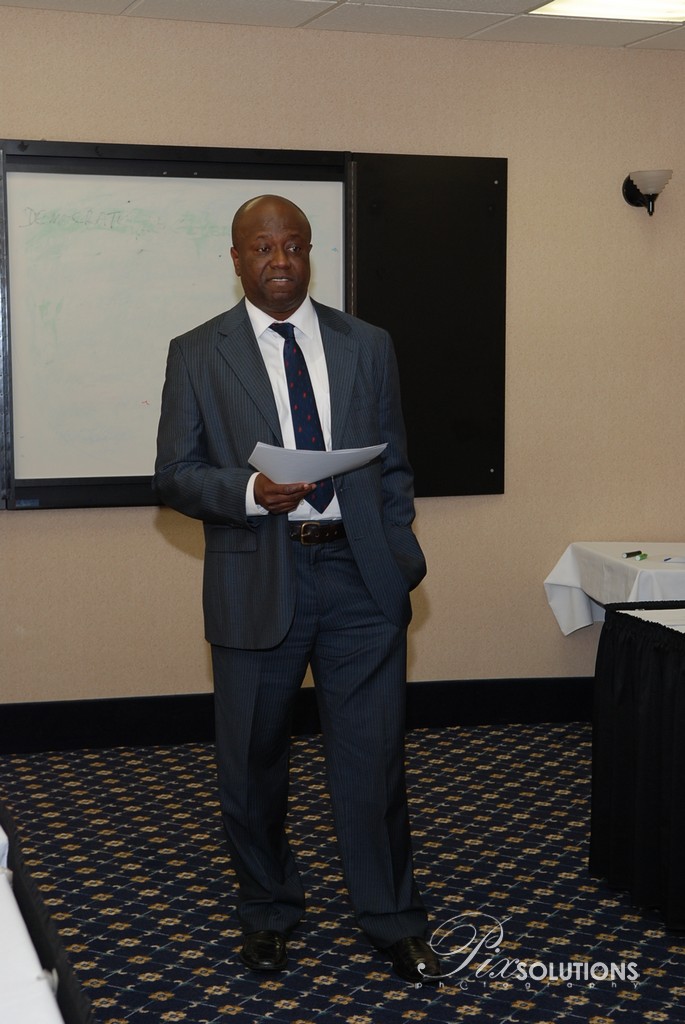

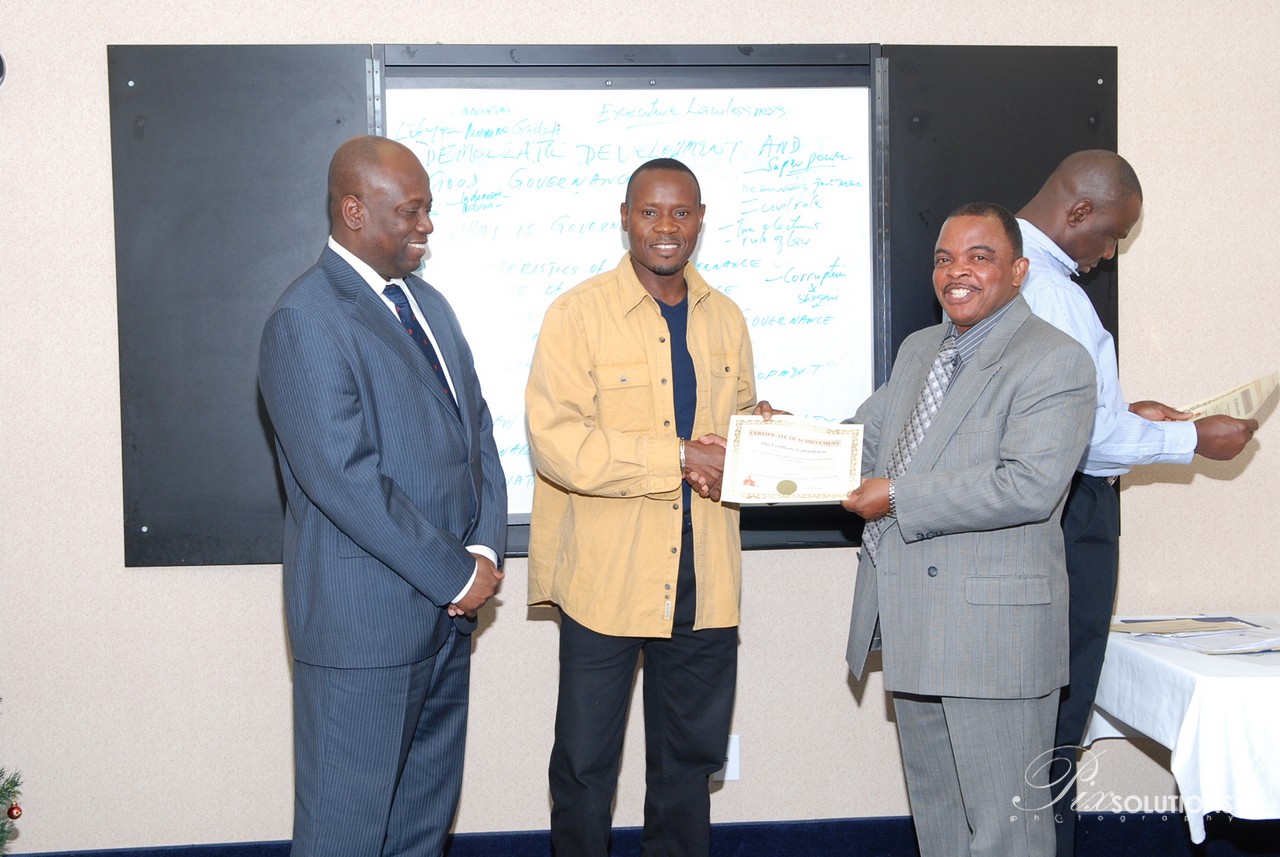

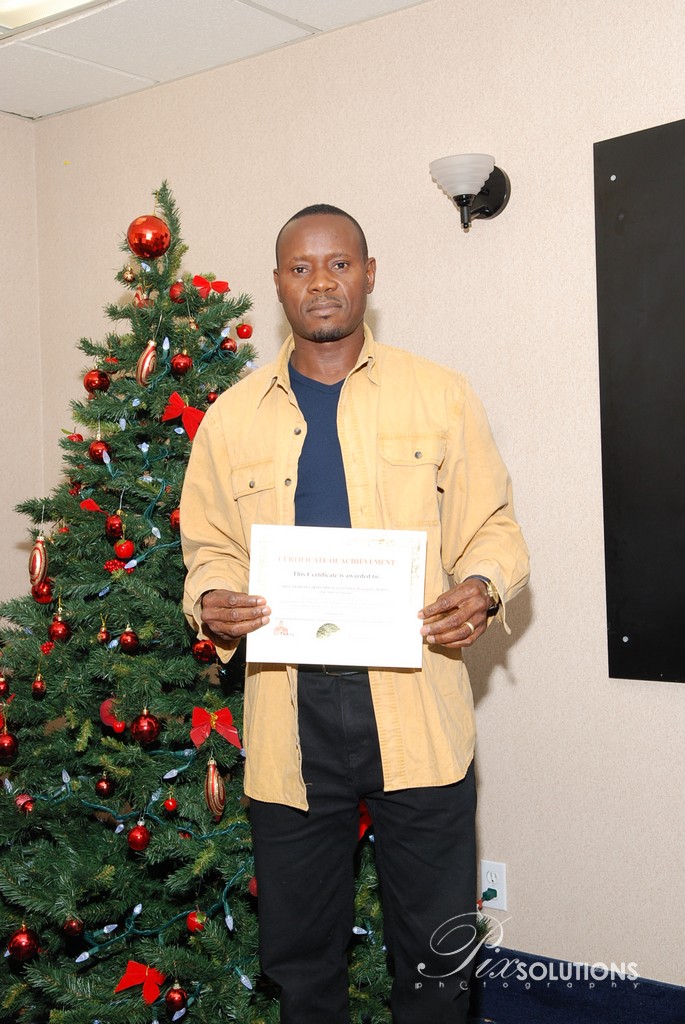

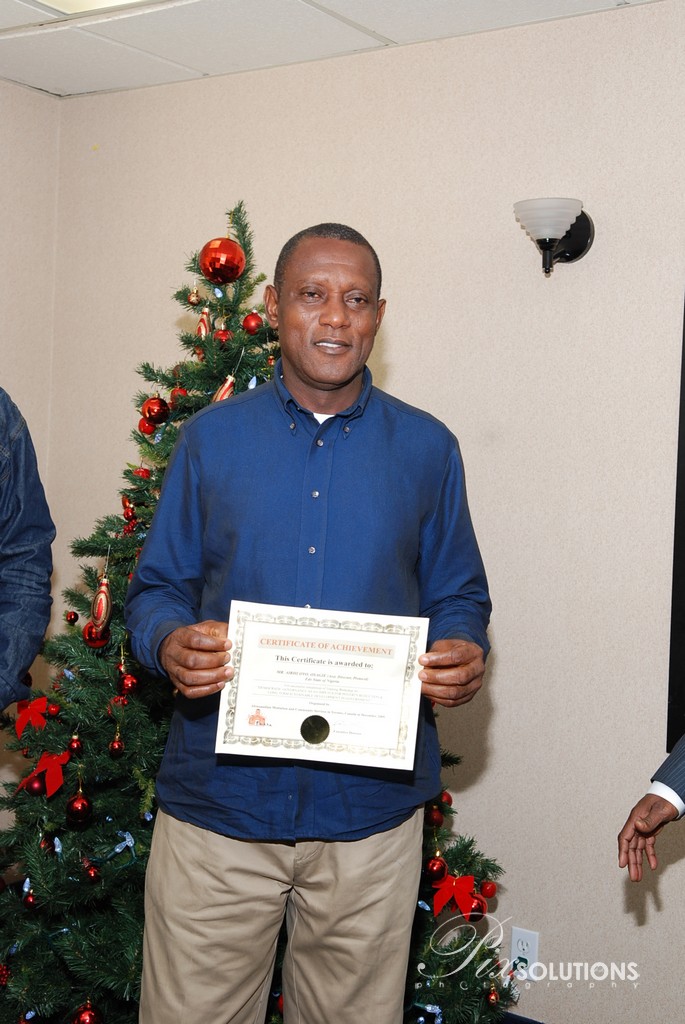

In a bid to extend its conflict resolution services to some parts of Africa, CMMS recently designed and initiated a training and skills development program in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), to be offered to State Institutions, Public Agents, Civil Society, and Non Governmental Agencies in some of these countries currently plagued by conflicts, civil unrests, kidnappings and militancy. In December 2008 CMMS planned and delivered a training program in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) for State Legislators from Edo State of Nigeria. The program was a success. Since the training, CMMS has been in close and continuous communications with the participants and there is the likelihood that there will be a follow up program with some other institutions in the state and other parts of the country. With the interest and the momentum, it is CMMS' objective to extend the program to other public institutions such as the police, the military, the prisons services and Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs). Below is a Toronto Based Community Newspaper “Nigerian Canadian News” coverage of the training program in its December 2008 Edition captioned on page 9 with the Program pictures at Centre spread of the newspaper as follows: EDO STATE LEGISLATORS IN TORONTO

FOR The Executive Members of the Edo State House of Assembly led by the Majority Leader of the Legislature, Hon. Frank Okiye were in Toronto recently to participate in a training workshop organized for them by “Canadian Multicultural Mediation Service (CMMS)”, a community based organization serving the African Canadian Community in the Greater Toronto Area of Canada. The title of the workshop was “The Role of the Legislature in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). The workshop lasted from November 17th to 21st 2008. Before progressing to the subject matter of the training workshop which was “The Role of the Legislature in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)”, the Legislators were first taken through relevant topics in Conflict Management with emphasis on the following areas of mediation: “Overview of Mediation” which includes; Definition of Mediation and its prospects, When is Mediation appropriate and what issues are mediatable, Helping Disputants Consider mediation ideas, Dynamics of Conflict Escalation, Preparation and Assessment, Techniques and Skills of a Mediator, Communication Skills of a Mediator, Case Intake and Case Management, Win/Win Problem Solving, The Mediation Process, The Mediator’s Role, Helping Disputants consider BATNA (Better Alternative to Negotiated Agreement), Cultural Differences in Conflict, Co-Mediation Process, Caucusing, Role Plays, Debriefing, Memorandum of Understanding, Supportive Feedback techniques, Follow up after mediation, etc. The following approaches to conflicts using the “orange example” were also discussed at the training workshop.

In the second phase of the workshop “Role of the Legislature in Alternative Dispute Resolution”, the following topics were covered.

The new breed of Legislators from this frontline state of Nigeria led by the charismatic Majority Leader; Hon. Frank Okiye surprised the training team with their enthusiasm, dedication, attention to detail and seriousness of purpose throughout the workshop. Their contribution and interactive role throughout the workshop was very encouraging. While awaiting their arrival in Canada for the workshop, our training team had pondered on how to make the lawmakers who have tasted the corridors of power, opulence, pleasure and great exposure confine themselves to another classroom environment. We were proven wrong by all of the above qualities exhibited by the Legislators at the training. Speaking on behalf of the Delegation, the Majority Leader, Hon. Frank Okiye expressed their appreciation to the organizers for a well-organized training package put together for the workshop. He said they found the seminar useful, and a learning experience. The leader further commented that the planners of the event had made their stay welcoming in Canada and that it was difficult for them to go back, but however, the program had made their return all the more imminent so as to put to practice what they have learned. He said they were looking forward to further studying the materials provided upon their return, and were confident that the learning and experience would be applied and shared with their colleague and staff on their return to Nigeria. Other participants in their individual conversations with the organizers and facilitators were grateful about what the program meant to them as Legislators. In summary they said they found that ADR would be a useful dimension to the work they do as lawmakers, and that what they would do on their return is to pursue opportunities for others to be exposed to such great learning, which they believe will create greater depth and impact on the work they do as Lawmakers, and also help their constituents. In closing, Mr. Robin Edoh, the Executive Director of CMMS, who himself is a York University trained Mediator, a member of the Ontario Institute of Alternative Dispute Resolution, a member of the Ontario Community Mediation Network, a holder of Advanced, Intermediate and Basic Certificates in “Alternative Dispute Resolution”, “Victim Offender Mediation”, “Basic Civil Procedure for Non-Lawyer Mediators”, and “Train the Trainer in Interpersonal Mediation” and who himself also facilitated at the workshop, thanked the Legislators for the good leadership example and qualities they displayed throughout the workshop. He said he and other members of his team were greatly moved by the Legislators’ charisma, patience, dedication, self discipline, attention to detail, and above all, their useful contribution and interactive style throughout the training. He encouraged the Legislators to come back for another workshop on “Victim Offender Mediation” in future, which he described as a different branch of Alternative Dispute Resolution. To view the activities of Canadian Multicultural Mediation Service (CMMS), you may visit their website at www.metros.ca/CMMS. Below are Pictures of the ADR Training Program

of the Edo State Legislators in Toronto Canada for your viewing.

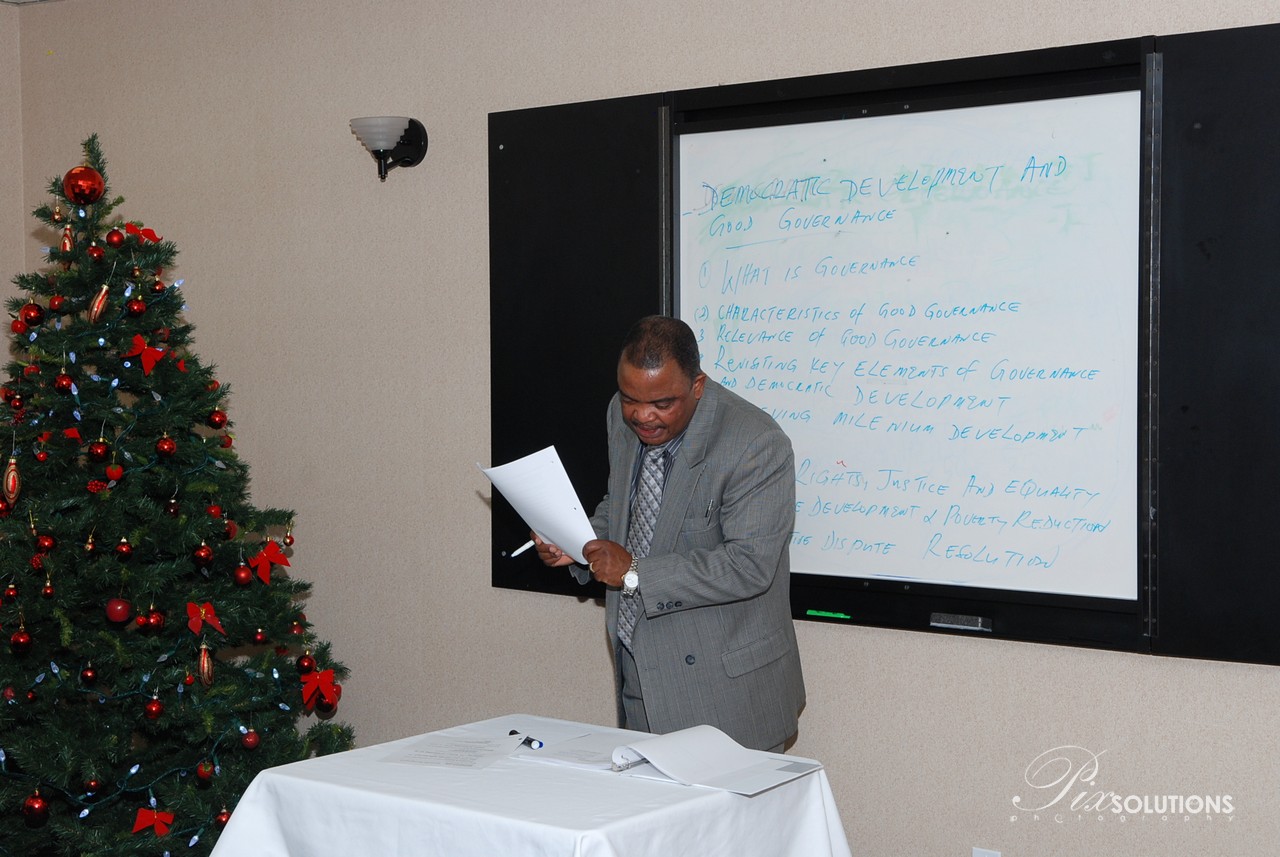

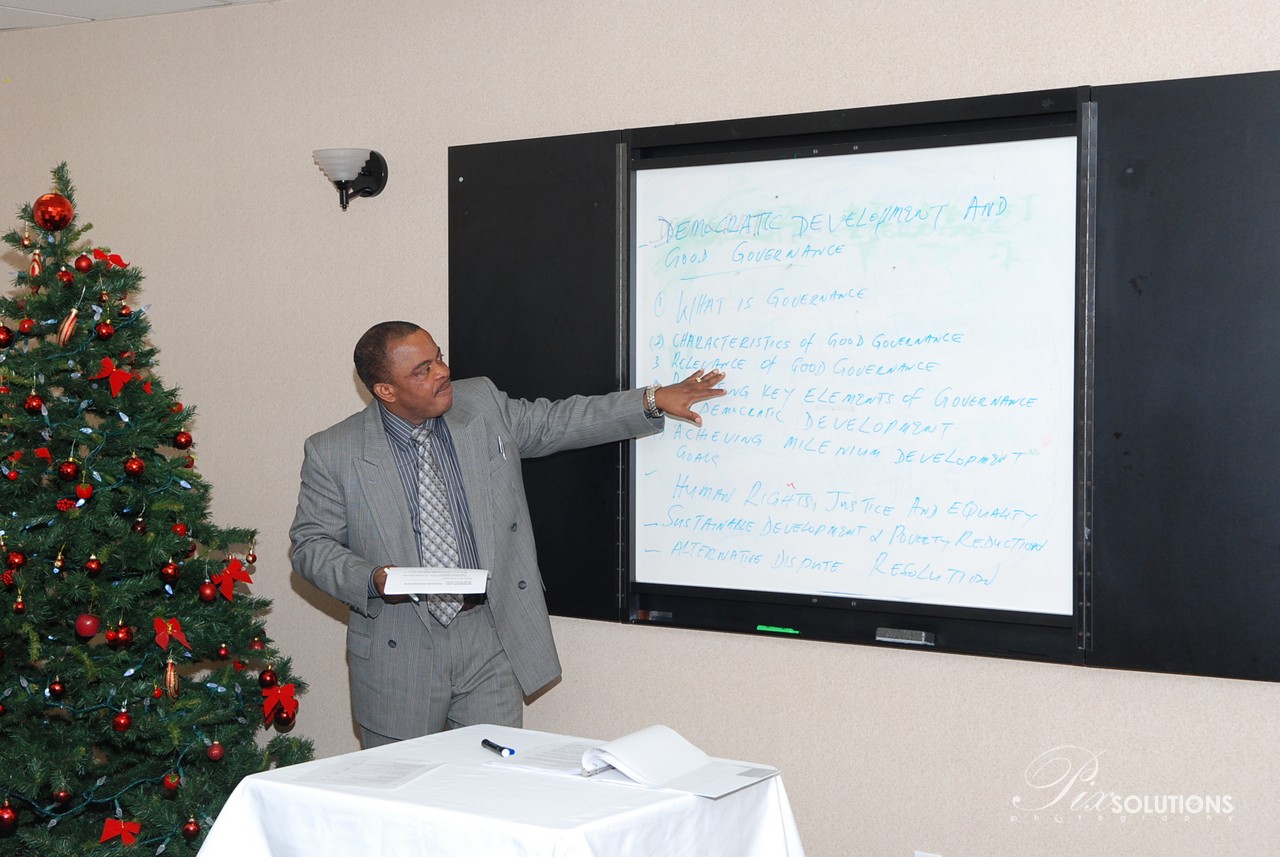

EDO STATE LEGISLATORS IN TORONTO FOR The Executive Members of the Edo State House of Assembly led by the Deputy Speaker, Hon. Aigbogun O. Levis, Chairman, Committee on Tenders Board were in Toronto Canada recently to participate in a training workshop organized by "Canadian Multicultural Mediation Service (CMMS). The title of the workshop this time was "Democratic Governance: An Impetus For Sustainable Development In Government". One year before now, the Hon. Members of the Edo State House of Assembly had attended another workshop organized by the same organization. The title of that workshop was, "Role of the Legislature in Alternative Dispute Resolution". Both workshops were hands on and very interactive in nature. The following areas were covered during the training workshop on "Democratic Governance: An Impetus to Sustainable Development in Government": Framework for Training for November 2009 SECTION ONE: Democratic Development & Good Governance COMPONENTS

SECTION 2: Human Rights, Justice & Equality COMPONENTS

SECTION 3: Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction COMPONENTS

SECTION 4: Alternative Dispute Resolution COMPONENTS

SECTION 5: Civil Society, Local Governance & Sustainable Development COMPONENTS

Please view Photos and Activities during the training workshop.

The general content of this website are All rights reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Canadian Multicultural Mediation Service |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1110 Finch Ave West, Suite 224 North York, Ontario M3J 2T2 Tel: (416) 203-2869 Fax:(416) 203-1881 CMMS@bellnet.ca |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||